Exploring the Decline of Open Water in Hesaraghatta Catchment

Updated Date: 09 Feb 2024

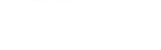

The lakes within the Hesaraghatta catchment underwent detailed analysis using Landsat imagery. Our scrutiny identified a sharp decline in the open water of the lakes in the Hesaraghatta catchment, indicating a serious water storage crisis.

Open water is the visible area of water in lakes or reservoirs that is detected and measured using satellite imagery. Clouds, trees, aquatic vegetation and buildings can obscure the detection of water by the satellite.

NASA’s Landsat satellite imagery data is used to detect open water. Landsat satellites have captured images of the Earth’s land surfaces since 1972, and all that data is available freely for analysis.

Decline of Open Water in Hesaraghatta Catchment

The monsoon (Jun-Dec) of 2022 recorded 1263mm of rain, a 94% deviation from normal, breaking all previous records and marking the highest rainfall in 122 years. Additionally, 2021 also had record-breaking rainfall with 1118mm, 72% above normal, making it the second-highest rainfall in 121 years after 1903.

With such abundant rainfall, one would expect ample surface storage to last for several years, providing a buffer against fluctuations in rainfall. However, this expectation does not hold true for the lakes of the Hesaraghatta catchment.

By April 2023, the open water had sharply declined by half compared to October 2022, signalling a significant loss of water retention capacity in the lakes of the Hesaraghatta catchment. The image below shows the open water decline.

This decline can be attributed to several factors, including siltation, the Karnataka Forest Department’s (KFD’s) commercial fuelwood plantation on large tracts of lakebeds, overuse of groundwater, and unscientific soil/silt excavation on the lakebed for sand mining and brick-making.

The drone image (taken by Paani) to the right shows Tippuru Thimmamana kere (i.e. Lake) with little water storage in Aug 2023 despite the deluge of 2022.

Another minor factor for open water decline may also be due to increased aquatic vegetation like water hyacinth and Azolla on some lakes, which receive untreated wastewater from both towns and industries.

These issues have long been recognised as threats to the water bodies. However, the rapid decline shown by satellite imagery suggests that the measures taken to address them have been highly inadequate.

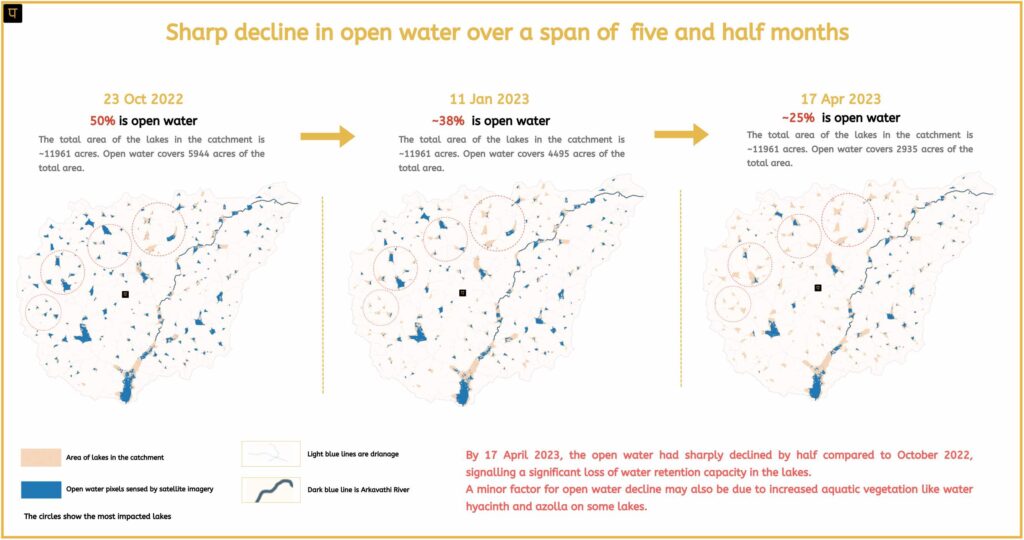

The drone image to the left (taken by Paani) shows Sonnenahalli Lake with little water storage in Aug 2023 despite the deluge of 2022.

In this era of climate change, rainfall patterns have become increasingly erratic, with sudden, intense downpours followed by prolonged drought-like conditions. For instance, the Hesaraghatta catchment (Doddaballapura region) experienced a deluge in 2022 and was drought-hit in 2023, as declared by the Government of Karnataka in Sep 2023.

In such circumstances, prioritising water storage becomes crucial to counteract water scarcity during dry spells. Maximising water retention during intense rainfall events is not merely advisable; it is essential for ensuring water security and resilience in the face of climate variability.

However, rather than prioritising local water storage in the catchment, the Karnataka government is implementing the Yettinahole Integrated Drinking Water project, which involves transporting water from the Netravathi River, located ~280 km away in the eco-sensitive Western Ghats.

The project is ecologically and economically unsound.

With an estimated cost of 24,000 crores, this project aims to provide water to parched areas, including Hesaraghatta Lake. Hesaraghatta Lake is slated to receive 0.7 TMC of water (0.8 TMC as per the Yettinahole Detailed Project Report).

The project’s implementation has resulted in an unquantified submergence of forests and treecover in the western ghats and a significant reduction in the flow of the Netravathi River, not to mention the humanitarian crisis of the tribal families.

The image to the right shows the construction work on a project in Sakleshpura Taluk, Hassan District.

From both environmental and economic perspectives, prioritizing local water storage over transporting it from distant sources is logical, rational, and cost-effective. The tagline of the Central Government’s recent campaign, “catch the rain, where it falls, when it falls,” underscores the urgent need to implement such measures.

RIVER BASIN

DAMS & FLOW

POLLUTION

GROUNDWATER

STRAWS

BIODIVERSITY

RAINFALL FLOODS & DROUGHT

RESTORATION